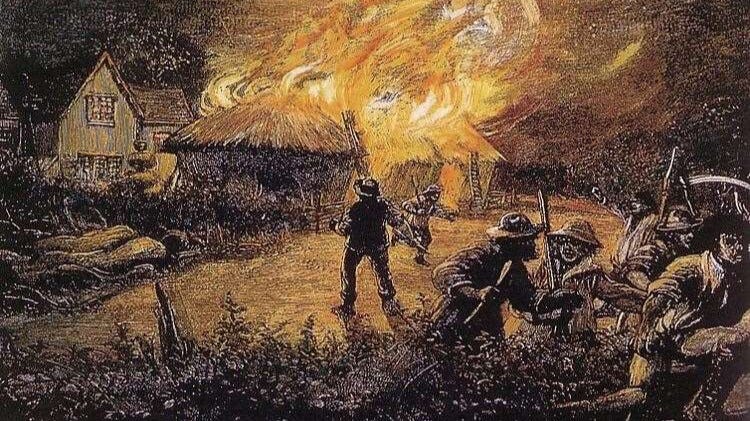

Image: Barns burn during The Swing Riots, 1830

This is an imaginal telling, woven from the threads of a dream—when an old river whispered my name and the ancestors leaned a little closer to my ear. It is not an attempt to recover facts, but to enter the living myth of those who came before me.

My great great uncle Horatio Packman was the last basket weaver in St Mary Cray, a small market town in county Kent. He lived in Viaduct Cottage with the River Cray running right through his garden. He would soften his willow in her flow. The name Packman once meant peddler, wanderer, and most sacred of all, storyteller. It was said Horatio told stories as he wove—weaving while weaving.

Maybe on a dark winter’s night, in some other kind of time, he told me this one.

Horatio sits by the river he called Old Sedge, willow shavings at his feet, his fingers threading reed through time. He weaves not just a basket—but a story-vessel, a memory-carrier. It holds what the Great Cray-Mother will never forget.

You see this weave, boy?

This crossing of wet willow and ash?

This isn’t just a basket for apples or coals.

This here is a truth-holder.

Sit close to me.

The river’s kinder when you listen.

I’ll tell you something they won’t print in books.

There were once two brothers—William and Henry Packman, born in the flint-boned soil of Kent. They weren’t much older than a robin’s second clutch when the fires started burning through the southern fields.

The year was eighteen-hundred-and-thirty, and new machines—iron-mouthed threshers—had arrived like rough gods, chewing up the work of a hundred men in a single day. Pockets grew empty. Bellies ached.

Then the letters came. They were signed, always, Captain Swing.

“Destroy your machines, or the night will remember you.”

“Pay us fair, or the barns will bloom with fire.”

No-one ever saw him, but all felt him. He was the wind in the hedgerows, hoofbeats in snow, a name that passed from lips to lips like a whisky flask in winter.

Now William and Henry—our blood, mine and yours—they didn’t write those letters. No, but they heard the call. That they did, indeed.

Heard them in the cracked voice of their father. Heard them in the silence of supperless nights. Heard them in the twitch of their young hands, yearning for action and to light a flame where justice wouldn’t reach.

They held a powerful energy, those lads. Just like this basket, here—see? But always remember, you don’t have to make fire to carry its ashes.

There was a man named Bishop, who turned King’s Evidence.

Bishop—Ha! Even the name tastes of holy lies.

He swore against our brothers, claimed they’d struck the match. But it was Bishop who had the plan. Bishop who had the means. Bishop who left that barn glowing like a swallowed star.

Yet it was our boys who paid. With the sun drawing low on the horizon, they sat on their coffins, barefoot in the cold, hard dirt of Penenden Heath, looking up at gallows and noose.

One of them—Henry, I think—said,

"That looks an awful thing. Ain’t that the line that splits a soul?”

In a strange twist, when the hoods were placed over their heads, William found his hands untied. Before the noose touched his neck, he tore his hood off, declaring that he wished to see the gathered crowd.

“Let me see the faces that will remember mine.”

It was Christmas Eve, but when that rope whipped tight, no bells rang for Jesus. No sound at all but the wind whispering a name through the hawthorn:

Captain Swing. Captain Swing. Captain Swing.

Well, the boys swayed back and forth for more than an hour, before they were cut down by their father and taken to be buried in Canterbury.

Now you might ask, was Captain Swing real? I tell you, boy, he was more than real. He was every man who ever tilled the land with bloody and blistered hands. He was every mother who fed her babes with prayers and nettles.

He was an idea with no face and many tongues.

You see this basket? Weaved tight like that hanging rope, ain’t it? Every strip crisscrossed like truth through shadow. Still, it breathes, it breathes easy. It holds everything lightly without choking the life out of it. Just like a story, eh?

It’s why I keep the willow wet in the river. A story must stay supple like that, too.

So as I tell you this tale, I bend withies with every word. So you’ll remember. So you’ll carry it. Because we so often forget the ones who burn.

But us? No. Not us. We can weave them back into the shape of something—something that can hold the weight of grief and ashes.

Now pass me that knife, boy. It’s time to bind the rim. When this basket’s done, you can take it with you.

Fill it with kindling. Fill it with images. Fill it with meaning.

The Swing Riots were an uprising of agricultural workers that took place in southern England during the autumn and winter of 1830–1831. They were sparked by the introduction of threshing machines, which replaced manual labour during harvest time, leading to widespread unemployment. Protesters would destroy the machines, burn hayricks, and send threatening letters signed by the mythical ‘Captain Swing.’

William (20) and Henry (18) Packman were the last to be hanged at Penenden Heath, on December 24, 1830.

References:

Bromleag, 2020. The Last Basket Maker in St Mary Cray.

Kent Online, 2020. The Story of the Three Men Hanged at Penenden Heath during the Swing Riots.

The National Archives, 2020. Captain Swing letters.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider joining our mythopoetic community at The Fifth Direction. Through breath, meditation, poetry, storytelling and ritual, we reclaim our mythic imagination and celebrate the return to soul.

The Fifth Direction is a welcome community for everyone. This includes people of all genders, faiths, backgrounds, orientations, ages and abilities.

This project is entirely supported by you, the reader and the listener. If joining the community isn’t your path, perhaps you could consider a small contribution.

I can feel that story in my bones! Thank you for telling it!

Your story is probably happening again now in The USA, by Trump, Vance and MuskRat dumping social welfare needed for survival by so many.

Thank you for this allegory. We must know the past to survive in the present.

Love from Australia